26th Sunday in Ordinary Time (A)

100th World Day of Migrants and Refugees

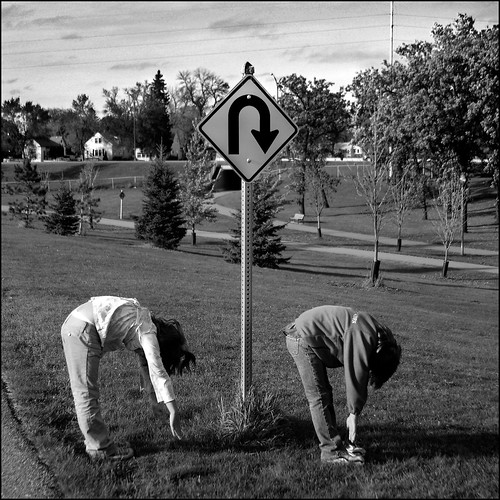

Picture: cc gfpeck

Sisters and brothers, have you ever experienced for yourself what a difference a U-turn can make? Have you ever, for example, found yourself in a car going in the wrong direction? Maybe you took a wrong turn. Or maybe you missed your exit on a highway. What to do? You need to turn around. But you can’t do that unless and until you find a U-turn. In a small city like Singapore, this is usually not too much of a problem. U-turns are relatively common. But imagine travelling in a strange country. And having to drive many kilometres going the wrong way. All because you can’t find a U-turn. It can be quite frustrating. Even scary. Especially if your car is running low on fuel. Or you’re facing an emergency of some sort. In such situations, a U-turn can make all the difference. Even the difference between life and death.

U-turns that make the difference between life and death. This is also what we find in our readings today. In the first reading, we find people making U-turns of two different types. The upright man renounces his integrity to commit sin and dies. The sinner renounces sin to become law-abiding and honest. And so finds life. The upright man makes a U-turn towards death. The sinner towards life. The first sabotages himself. The second wins salvation. In each case it is the direction of the U-turn that makes all the difference. The difference between death and life.

In the gospel too, U-turns are what make all the difference. A father asks two sons to work in his vineyard. One son refuses. But later changes his mind and goes. Another son does the opposite. He agrees. But then changes his mind and doesn’t show up. Both sons make U-turns. But in opposite directions. The first son toward obedience. The second disobedience. But the story is, of course, a parable. It’s not just about obeying an earthly father. But our Father in Heaven. It’s not just about working in an ordinary vineyard. But the Vineyard of Life Eternal. Here, as in the first reading, obedience leads to life. Disobedience results in death. And, again, it’s the direction of the U-turn that makes all the difference.

That much is clear. And yet, sisters and brothers, do we really know what it means to be obedient? Or disobedient? Do we really know what it looks like to be heading towards life? And what it looks like to be going in the opposite direction? Do we really know? Perhaps this may sound to us like a very silly question? After all, we’re respectable church-going people. Of course we know what it means to be obedient to God! Of course we know what it looks like to be on the way to life!

And yet, in the gospel, it is precisely the people who think they know who really don’t. That’s the reason why Jesus tells the parable in the first place. To show the chief priests and elders of the people that they don’t really know what it means to be obedient. That, even though they may pride themselves on their own knowledge and practice of the Law, they are actually heading in the wrong direction. Not towards life. But towards death.

So what does obedience look like? How do we know whether or not we are headed in the right direction? To find the answer to this question, we need to look more closely at our readings. In the first reading, God poses this question to the people: Is what I do unjust? Is it not what you do that is unjust? What is this distinction that God is making? In the eyes of God, what is the difference between the just and the unjust?

Again, the difference has to do with U-turns. The justice of God consists in God’s willingness to allow the sinner to repent. In contrast, God considers the people unjust because they refuse to let this happen. They refuse to give others the opportunity to turn their lives around. To make U-turns. And isn’t this true of the chief priests and elders in the gospel? Thinking that they themselves are already on the right path, they refuse to entertain the possibility that tax collectors and prostitutes could repent and find life. It never occurs to these self-righteous men that public sinners could actually be making their way into the kingdom of God before them.

Sisters and brothers, isn’t this what makes the difference between true justice and injustice? Between obedience and disobedience? Between life and death? The willingness to allow others to make U-turns. The readiness to give those heading in a wrong direction the opportunity to turn their lives around. The responsorial psalm summarises this in a single word. Mercy. Remember your mercy, Lord. The psalmist prays. Do not remember the sins of my youth. In your love remember me… In other words, Lord, be merciful to me. Give me the opportunity to turn my life around. Allow me the chance to make a U-turn unto life.

Remember your mercy, Lord. This poignant prayer of the psalmist, which we can so easily make our own, finds its answer in the second reading. Here St. Paul describes for us what God’s mercy looks like in the flesh. Again, it has to do with U-turns that make all the difference. Though his state was divine, Christ Jesus, in his mercy, chose to make a detour in the direction of our own sinful condition. He chose to empty himself. Even to the point of accepting death on a cross. But God worked a U-turn of his own. God raised him high. Turned around the scandal of his dying. And transformed it into the glory of unending life. Gave him the name which is above all other names. So that, through him and with him and in him, those of us headed in the wrong direction might be able to turn our lives around. If only we would praise his name. If only we would follow in his steps. If only we would immerse ourselves in his mercy. And share it with others.

To show mercy to others. To allow them the opportunity to change their lives for the better. To give them the chance to make a U-turn in the direction of new life. This is what obedience looks like. This is what God has done for us in Christ. This is also what we, in our turn, are called to do for others. And it’s fitting that we should be reminded of this especially today. As we celebrate the 100th World Day of Migrants and Refugees. A day when we consider the many people in the world whose lives have been turned upside down. People displaced from their homes for one reason or another. People crying out for the opportunity to turn their lives around again. People in need of mercy... Not just those living in faraway lands. But also those who have somehow found their way to our shores. Not just those suffering from the more obvious violence of war and natural disasters. But also those fleeing from the more subtle cruelty of an oppressive global economy. Forced to sell their labour, and sometimes even their bodies, in exchange for poor wages and harsh treatment.

Sisters and brothers, could it be that if we were only to look carefully around us, we would find many still needing to turn their lives around? What can we do to show them mercy? To help them make a U-turn unto new life today?

U-turns that make the difference between life and death. This is also what we find in our readings today. In the first reading, we find people making U-turns of two different types. The upright man renounces his integrity to commit sin and dies. The sinner renounces sin to become law-abiding and honest. And so finds life. The upright man makes a U-turn towards death. The sinner towards life. The first sabotages himself. The second wins salvation. In each case it is the direction of the U-turn that makes all the difference. The difference between death and life.

In the gospel too, U-turns are what make all the difference. A father asks two sons to work in his vineyard. One son refuses. But later changes his mind and goes. Another son does the opposite. He agrees. But then changes his mind and doesn’t show up. Both sons make U-turns. But in opposite directions. The first son toward obedience. The second disobedience. But the story is, of course, a parable. It’s not just about obeying an earthly father. But our Father in Heaven. It’s not just about working in an ordinary vineyard. But the Vineyard of Life Eternal. Here, as in the first reading, obedience leads to life. Disobedience results in death. And, again, it’s the direction of the U-turn that makes all the difference.

That much is clear. And yet, sisters and brothers, do we really know what it means to be obedient? Or disobedient? Do we really know what it looks like to be heading towards life? And what it looks like to be going in the opposite direction? Do we really know? Perhaps this may sound to us like a very silly question? After all, we’re respectable church-going people. Of course we know what it means to be obedient to God! Of course we know what it looks like to be on the way to life!

And yet, in the gospel, it is precisely the people who think they know who really don’t. That’s the reason why Jesus tells the parable in the first place. To show the chief priests and elders of the people that they don’t really know what it means to be obedient. That, even though they may pride themselves on their own knowledge and practice of the Law, they are actually heading in the wrong direction. Not towards life. But towards death.

So what does obedience look like? How do we know whether or not we are headed in the right direction? To find the answer to this question, we need to look more closely at our readings. In the first reading, God poses this question to the people: Is what I do unjust? Is it not what you do that is unjust? What is this distinction that God is making? In the eyes of God, what is the difference between the just and the unjust?

Again, the difference has to do with U-turns. The justice of God consists in God’s willingness to allow the sinner to repent. In contrast, God considers the people unjust because they refuse to let this happen. They refuse to give others the opportunity to turn their lives around. To make U-turns. And isn’t this true of the chief priests and elders in the gospel? Thinking that they themselves are already on the right path, they refuse to entertain the possibility that tax collectors and prostitutes could repent and find life. It never occurs to these self-righteous men that public sinners could actually be making their way into the kingdom of God before them.

Sisters and brothers, isn’t this what makes the difference between true justice and injustice? Between obedience and disobedience? Between life and death? The willingness to allow others to make U-turns. The readiness to give those heading in a wrong direction the opportunity to turn their lives around. The responsorial psalm summarises this in a single word. Mercy. Remember your mercy, Lord. The psalmist prays. Do not remember the sins of my youth. In your love remember me… In other words, Lord, be merciful to me. Give me the opportunity to turn my life around. Allow me the chance to make a U-turn unto life.

Remember your mercy, Lord. This poignant prayer of the psalmist, which we can so easily make our own, finds its answer in the second reading. Here St. Paul describes for us what God’s mercy looks like in the flesh. Again, it has to do with U-turns that make all the difference. Though his state was divine, Christ Jesus, in his mercy, chose to make a detour in the direction of our own sinful condition. He chose to empty himself. Even to the point of accepting death on a cross. But God worked a U-turn of his own. God raised him high. Turned around the scandal of his dying. And transformed it into the glory of unending life. Gave him the name which is above all other names. So that, through him and with him and in him, those of us headed in the wrong direction might be able to turn our lives around. If only we would praise his name. If only we would follow in his steps. If only we would immerse ourselves in his mercy. And share it with others.

To show mercy to others. To allow them the opportunity to change their lives for the better. To give them the chance to make a U-turn in the direction of new life. This is what obedience looks like. This is what God has done for us in Christ. This is also what we, in our turn, are called to do for others. And it’s fitting that we should be reminded of this especially today. As we celebrate the 100th World Day of Migrants and Refugees. A day when we consider the many people in the world whose lives have been turned upside down. People displaced from their homes for one reason or another. People crying out for the opportunity to turn their lives around again. People in need of mercy... Not just those living in faraway lands. But also those who have somehow found their way to our shores. Not just those suffering from the more obvious violence of war and natural disasters. But also those fleeing from the more subtle cruelty of an oppressive global economy. Forced to sell their labour, and sometimes even their bodies, in exchange for poor wages and harsh treatment.

Sisters and brothers, could it be that if we were only to look carefully around us, we would find many still needing to turn their lives around? What can we do to show them mercy? To help them make a U-turn unto new life today?